The Space to Have a Voice

There are many ways to deny someone a voice — shaming, guilting, intimidating, dismissing, othering. But another, particularly pernicious way is to call into question their right to have a voice in the first place.

“If it’s so bad, go back to your country”

“You should be grateful”

“Oh, but you’re still here despite it all!”

As an immigrant, this is the brand I commonly interface when I comment on the deep dysfunction that American immigration system finds itself in. A system whose cracks the pandemic has ripped open, to reveal the gangrenous mess within.

Wait times for America Permanent Residency (aka, the Green Card) have long exceeded human lifespans for applicants unfortunate enough to be born in backlogged countries [1].

These long wait times have led to the children of these applicants aging-out of valid visa status, facing self-deportation at age 21 or the same grim pathways their parents are on [2].

Further, pandemic-induced slowdowns in paperwork processing have led to backlogs within the US borders at the USCIS, as well as at American consulates abroad [3].

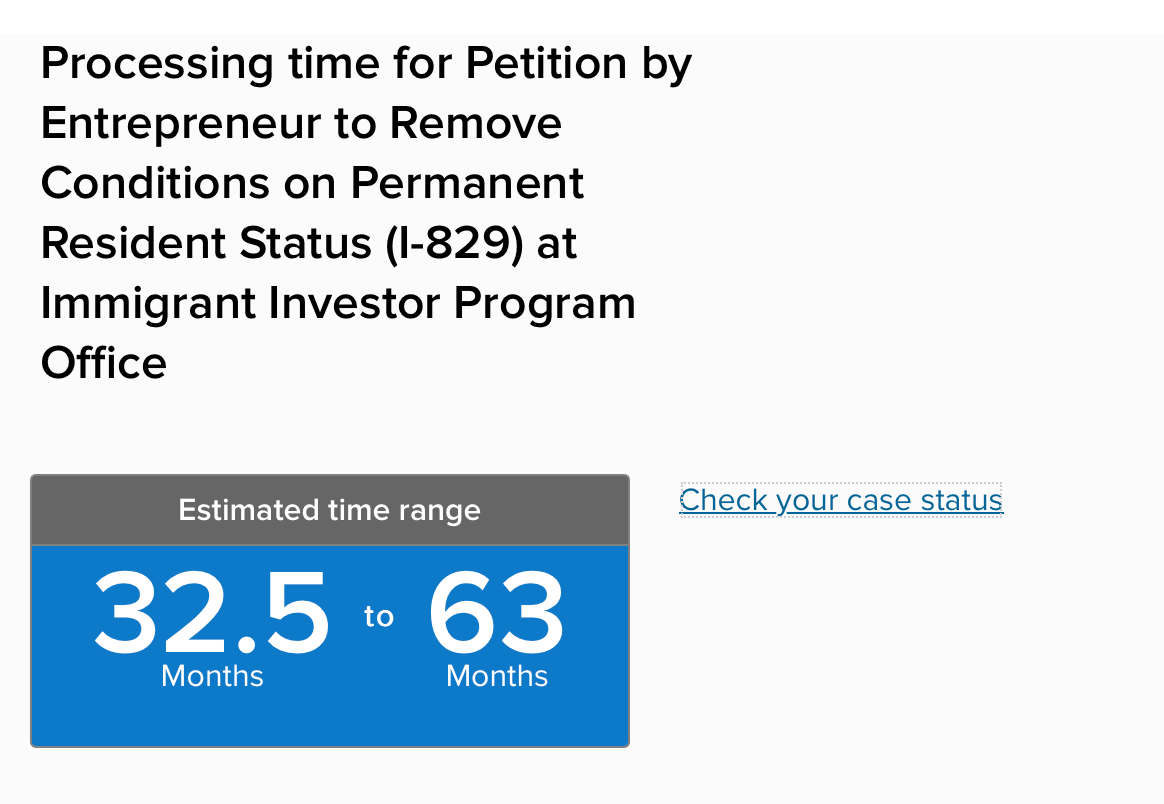

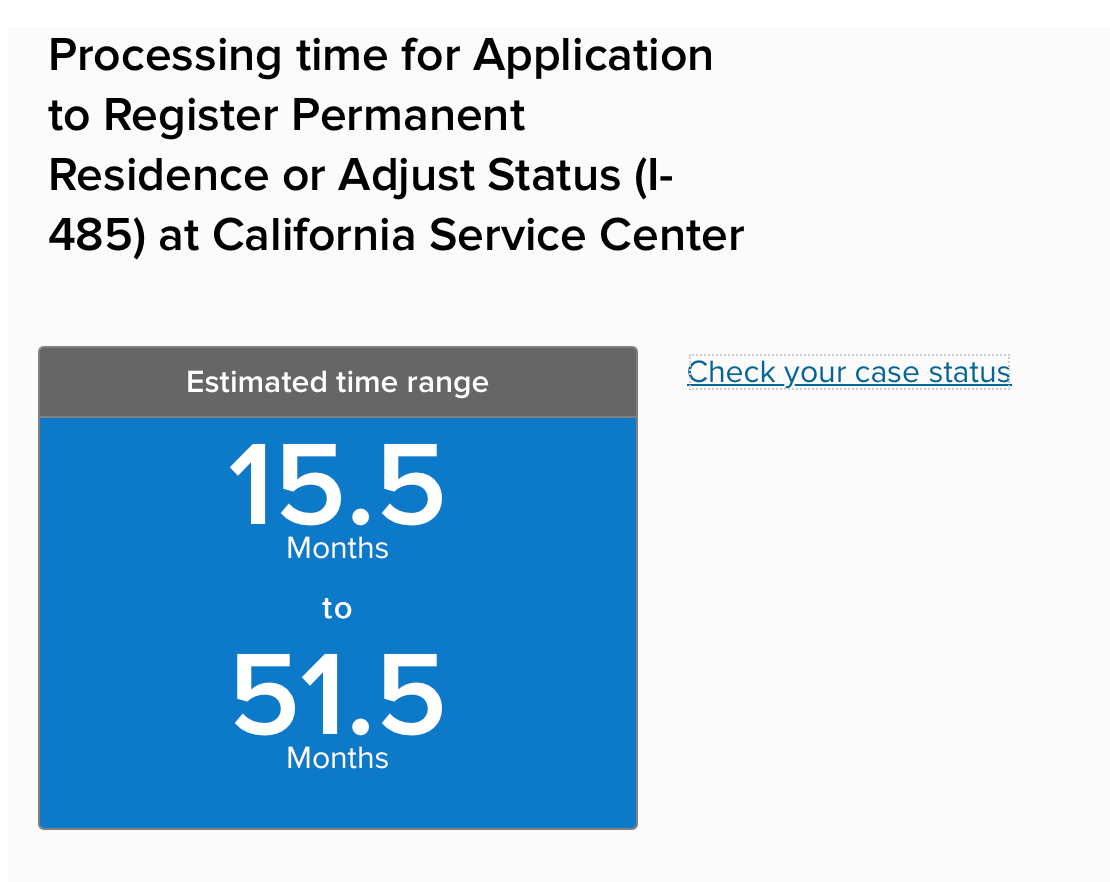

It has become common to see processing time estimates on the USCIS website that you have to do a double take on (screenshots below).

And worst of all, an estimated 100,000 unallocated Green Cards are set to expire in a space where demand already far outstrips supply [4].

With all of this being the reality, saying that the immigration system is badly, badly broken and in need of some serious reform should be a fairly uncontrovertial stance.

Indeed, it is hardly a matter of opinion anymore, it is plain fact.

But that’s not the point. It never has been.

It’s a question of who gets to criticise in America. Who gets to have a voice and who gets told that they’re just kicking up a fuss. As an immigrant talking about immigration issues, it becomes clear fairly quickly that you are part of the latter class.

Your existence in the US is seen as one that was “given” to you and therefore, voicing an opinion against the immigration system that gave you all you have, is to bite the hand that feeds. In one particularly memorable incident on Quora, I remember being told that as a foreign national who lived and worked in the US, how could I possibly have anything to complain about with immigration?

If all of this does not cause you to retreat from having a voice, you are obligated at the very least, to preface your criticism no matter how valid with emphatic assertions of your enduring gratitude to America and its society for all you have.

Don’t believe me?

Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman, Fiona Hill and Marie Yovanovich, three immigrants who have demonstrated plenty of integrity, patriotism and service to America, going so far as to put their lives and safety on the line in coming forward to testify against a sitting President, still felt the need to reaffirm their their commitment to this country. Their country!

It would have been one thing for them to reference their immigrant roots during their testimony which of course, is a pivotal fact of their lives and experiences. But there were clear assertions of gratitude and loyalty where none were needed. Their actions, their integrity and their courage that day should have been enough. [5]

If this was designed to prempt suspicion or clarify their stellar record going out to bat for their adopted country, it didn’t work. All immigrant witnesses had that fact used against them in right-wing media as they were maligned. Lt. Col. Vindman was the target of particularly vitriolic attacks.

Kamala Harris, a US born citizen who should consider her American-ness just as valid as anyone else’s, still pointed to America’s generosity to immigrants in conveying her gratitude to her Indian-born mother, Shyamala Gopalan Harris [6]. Just so we are clear, she conveyed gratitude on behalf of the person she was conveying gratitude to, in her victory speech.

Apparently immigrant indebtedness to America is a heritable condition.

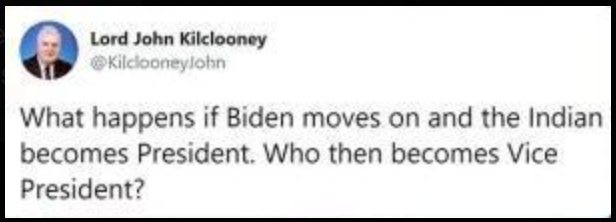

Despite this, her legitimacy as a candidate for VP was questioned on the basis of the fact that her parents were not American-born. In a particularly jarring incident where a non-American joined the othering of Kamala Harris, Lord Kilclooney, a member of the UK House of Lords, referred to Kamala Harris as “the Indian” in his since-deleted tweet.

It is clear that when you, as an immigrant, do anything remotely empowering, there is a pervasive culture in America that questions your place to do so. Whether that is occupying office, testifying in Congress or even merely drawing attention to the glaring immigration issues of the day on social media.

Anything other than a full-throated cheer of America and American-ness is seen as entitlement. It is inappropriate, unbecoming, unseemly. Kind of like putting your bare feet up, in your boss’s living room couch.

But here’s the thing…

Discontentment, criticism and grievances can co-exist with a deep sense of personal gratitude and belonging. If you ever take the time to talk to an immigrant about what their American experience has meant for them, you will realize just how grateful they are.

Immigrants, particularly visa holders are highly unlikely to take their American stint for grated, mostly because visas are necessarily time-limited and come with no future assurances of continuation.

My own criticism of immigration stems from the fact that I feel one with the issues of America. In any case, if immigrants who see the guts of a system that is simply invisible to the native population, don’t point out its flaws, who will? What better evidence of belonging than for an immigrant like me wanting to take on America’s baggage as my own?

Alongside my issues and concerns with the immigration system exists my gratitude for this experience. There is no tension here. The two manage to co-exist just fine within me. But all of this is between me and my relationship with the US. My gratitude for this experience is not something that anyone else can feel entitled to demand or examine, like a passport at a border checkpoint.

Being asked to exhibit that gratitude to America beyond the private realm is a demand that I do not take kindly to, because it is just a way to remind me of my “place”. A patronizing caricaturization of my existence of the US in which my palms will always be open in a gesture of receiving from the social largess of the US and that any shift from that submissive state of being is somehow a betrayal of all that I have. It is a co-opting of my efforts at creating a life for myself and reducing it to a handout.

And I resent that. Because saddling my shoulders with a vague sense of obligation is yet another way of telling me I don’t belong.

No one tells a person criticizing the DMV, that they are ungrateful for the ability to drive which as we all know is a priviledge accorded to us by the government and not a right. So, why are we telling immigrants who point out deep flaws in the immigration system to shut up and be grateful?

It is because at a fundamental level in the US, immigration is viewed as one big state benefit program. One that offers people like me a chance at opportunity. Immigrants are viewed as people who have won a golden ticket. An opportunity to escape from whatever wretched place we were unfortunate enough to be born in.

In the now infamous s*****le comment during his Presidency, Donald Trump did what he usually does- say the quiet part out loud.

And if this is the simplistic framework one operates in, the impatience or even downright aggression immigrants face in criticising the immigration system starts to make a lot of sense.

Think about it: How much patience would you have to listen to the whining of a person who won a million dollar lottery?

It starts to make even more sense when you factor in the “stealing jobs”, “overrunning the country” narratives that abound in this area. You’d have even lesser patience to tolerate that whining of you perceived a lottery winner’s financial windfall as coming from your wallet.

But immigrants didn’t win a lottery. We weren’t just plucked out of our miserable existence and transplanted to the US overnight. The whole enterprise of immigration with its layers and complexity do not boil down to a simple scenario of a giver and a receiver of benefits.

Becoming an immigrant in the US is not a windfall. It is not a gift. It is not a handout, a wonderful turn of fate or the product of government generosity. It is an accomplishment born of persistence, aspiration, contribution to society and bringing value in exchange for value.

It is the sort of exchange that reminds us of the classic “double-thank you” promise of capitalism.

Immigrants don’t just take. We pay taxes into systems we may not draw from for years (or ever!) like Social Security and Medicare. International students pay premium tuition at American Universities while being at the bottom of the barrel for scholarships and funding opportunities (the only exception being doctoral students).

The panic that US universities went into at many instance since the pandemic at the possibility of international student enrollment falling off a cliff should be all we need to realize that the whole enterprise of immigration with its layers and complexity cannot be boiled down to a simple scenario of a giver and a receiver of benefits. Their panic was very well-founded. International stuednts contributed $38.7 billion to the U.S. economy in 2019–20 [6].

And for many of us, US immigration agencies and the system are becoming not facilitators, but impediments to the eventual realization of their efforts. Coming to the US is not easy. It is not available as an option to everyone. And it is not cheap.

Even for people like me who actually did have a well-laid out pathway come to America in the first place, it takes typically at least a year’s worth of planning, significant expenditure, consistent and goal-oriented hard work and some serious persistence. Success is anything but guaranteed. And simply getting here is not success by itself...

When those of us who “make it” finally do arrive in the US, it is not until we get Permanent Residency, a process that even in the absence of backlogs routinely takes several years that our lives in the US are grounded in any real certainty.

Immigrants, even those of us who hold visas and aren’t Permanent Residents or citizens yet have a legitimate place in America society, politics and culture. We aren’t just guests who should “stay in their lanes” when we have lives in America for years, have worked to build its economy, paid taxes and have been impacted by the policies of state and local governments.

Our labor, financial contributions and the overall social value we have always brought to the US earn us a place at the table. A place that we will not request for, beg for, ask nicely for.

Because it not anyone else’s to give or take away.

References:

[1] https://www.cato.org/blog/150-year-wait-indian-immigrants-advanced-degrees

[3] https://www.boundless.com/blog/visa-backlog-biggest-barrier-immigrants/

https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/the-immigrant-witnesses-of-the-impeachment-hearings

[7] Image credits: Photo by Mika Baumeister on Unsplash